Building an EPUB translator for 200+ languages with Transformers

Here I describe the key steps in building an EPUB translator utility in Python. Other open source projects I found all use an API of Google Translate, DeepL Translate or ChatGPT. With the advances in AI and Transformer models, my idea is to create a locally-run ebook translator using multilingual translation models on a single GPU.

Transformers by Hugging Face 🤗

Transformers is an architecture that allows repurposing already pretrained models. A great introduction to Transformers specifically in relation to NLP is provided in Natural Language Processing with Transformers. Hugging Face provides convenient infrastructure for sharing, testing and running inference on models from the Hugging Face hub. We are interested in the machine translation category. For the scope of this project, fine-tuned models already exist. The simplest way to import the models in Python, including the tokenizer, is with the AutoTokenizer class:

import transformers

model = ctranslate2.Translator(model_path, 'cuda')

tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_path)

The model import may be different depending on the library – in this case CTranslate2. The model_path can point to a local directory or to a Hugging Face repository.

EPUB parsing

EPUB and PDF are the usual formats of ebooks. Because modifying PDFs is very difficult, the utility will support only EPUB for now. An EPUB consists of XHTML, CSS, image and other files. Python’s zipfile is able to deconstruct and reconstruct an EPUB file. BeautifulSoup4 is used for scraping the unzipped XHTML files.

The difficulties of processing EPUB files can be illustrated on some examples of XHTML. Well-structured EPUBs consist of several XHTML files that contain paragraphs, each paragraph with one or more sentences:

<p>“You thought it did,” said the old lady soothingly.</p>

<p>“I say it did,” replied the other. What’s the matter?”</p>

There is, however, no enforced standard. The following example is from a real book that contains a single XHTML with the entire text and with seemingly random formatting:

<p>

<span>They have freedom and autonomy.</span>

<span>Which is very ob</span><span><span>vious.</span></span>

</p>

<p>

<a></a><span>8 pe</span><span><span>rcent</span></span>

</p>

The < p > tags may contain other elements, sometimes only with a different class. It should be clear from the example that < span > tags can’t even be trusted to contain complete words. With a little foresight, we can conclude that 1:1 translation and retaining all the elements is impossible. Moreover, 8 percent in the example is a title of a chapter. Having no better differentiator than arbitrary class makes parsing harder.

Thankfully, I found that reconstructing on the level of < p > keeps most of the formatting intact, even though it removes sentence-level tags. This function illustrates how BeautifulSoup4 can be used to scrape the < p > tags:

def get_raw_texts(html_file_path):

html = read_html(html_file_path)

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

tags = soup.find_all('p')

texts = [tag.get_text() for tag in tags]

return texts

The function where an XHTML file is processed may look like this:

def process_contents(translator, html_object):

html_path = html_object.get('html_name')

html_content = epub_utils.read_html(html_path)

soup = BeautifulSoup(html_content, 'html.parser')

p_tags = soup.find_all('p')

translated = translator.translate(html_object.get('sentence_list'))

new_tags = apply_translated(translated, p_tags)

for original_tag, new_tag in zip(p_tags, new_tags):

original_tag.clear()

original_tag.append(new_tag.string)

return str(soup)

A preconfigured translator is injected to the function along with the html_object representing the file. The translator.translate returns the translated texts and apply_translated tries to rebuild the original structure with paragraphs. In the for loop, the original paragraphs are replaced by the translated ones and the soup object can then be written to the file.

Selected models

Several machine translation models that support at least 50 languages were considered. Two with the best output quality were selected: NLLB-200 and small-100. These models support around 200 and 100 languages, respectively. NLLB-200 comes in 600M, 1.3B and 3.3B variants. Although the implementation is identical, NLLB-200-1.3B was chosen for balance in quality, size and performance. The small-100 is based on the M2M100-418M model that did not meet the quality expectations and small-100 also has the benefit of smaller size.

More capable models exist, but resources are a limiting factor. For example, NLLB-200-3.3B takes roughly 15 GB of storage. Loading such a model into memory during inference is not feasible on most personal computers. Quantization was used to significantly reduce the storage and memory requirements without degrading the precision too much. Available CTranslate2 quantized NLLB-200 comes at 1.3 GB and requires around 2 GB of memory. My own quantization of small-100 was done using bitsandbytes as per the Hugging Face tutorial. Its quantized size is approximately 600 MB.

The models are hosted on my Hugging Face Hub.

Hardware

I decided later during the development to allow inference only on a GPU. Some configurations, though not all, can be run on CPU. CPU inference is slower by orders of magnitude, and won’t ever match a GPU. Though it can be optimised somewhat.

Nvidia (CUDA) GPUs work best with the setup. As for AMD, PyTorch and the extra dependencies introduced with quantized models are theoretically compatible according to their documentations. This is assuming a system with ROCm compatible AMD card in combination with the operating system. ROCm is available for most of RX and Pro cards on Windows. Options on Linux are even more limited.

Thanks to my friend Fjuro, I could test the behaviour on a Windows system with AMD card. The bitsandbytes quantization dependency reported “Only Intel CPU is supported by BNB at the moment”. CPU is another factor in compatibility. The dependency CTranslate2 accepts only hardware options in its constructor: device: Device to use (possible values are: cpu, cuda, auto). device=cuda throws an exception related to CUDA driver and device=auto defaults to CPU. The conclusion: ROCm support is patchy.

Translation

A model usually trims the input that exceeds the maximum token limit. The token count of a given input can be found from the tokenizer. In my experience, inputs with several sentences yield inconsistent results, often skipping sentences no matter the token constraint. For this reason, the utility translates sentence by sentence.

Because the contents of < p > tags may contain more sentences, the code must be able to split the text to individual sentences. This must work reasonably well for hundreds of languages. For sentence detection, I implemented NLTK’s punkt module:

import nltk

def download_nltk_resources():

try:

find('tokenizers/punkt_tab')

except LookupError:

nltk.download('punkt_tab')

def split_sentences(text):

return nltk.sent_tokenize(text)

The first function ensures that the punkt_tab module is downloaded. I did not yet test sentence splitting for languages that use different sentence endings.

Creating a bilingual book, where an original paragraph is followed by translated version is rather simple:

def process_contents(translator, html_object, bilingual):

...

for original_tag, new_tag in zip(p_tags, new_tags):

if new_tag.string is not None:

if not bilingual:

original_tag.clear()

original_tag.append(new_tag.string)

else:

original_tag.append(BeautifulSoup(str(new_tag), 'html.parser'))

original_tag.append(BeautifulSoup('<p><br/></p>', 'html.parser'))

return str(soup)

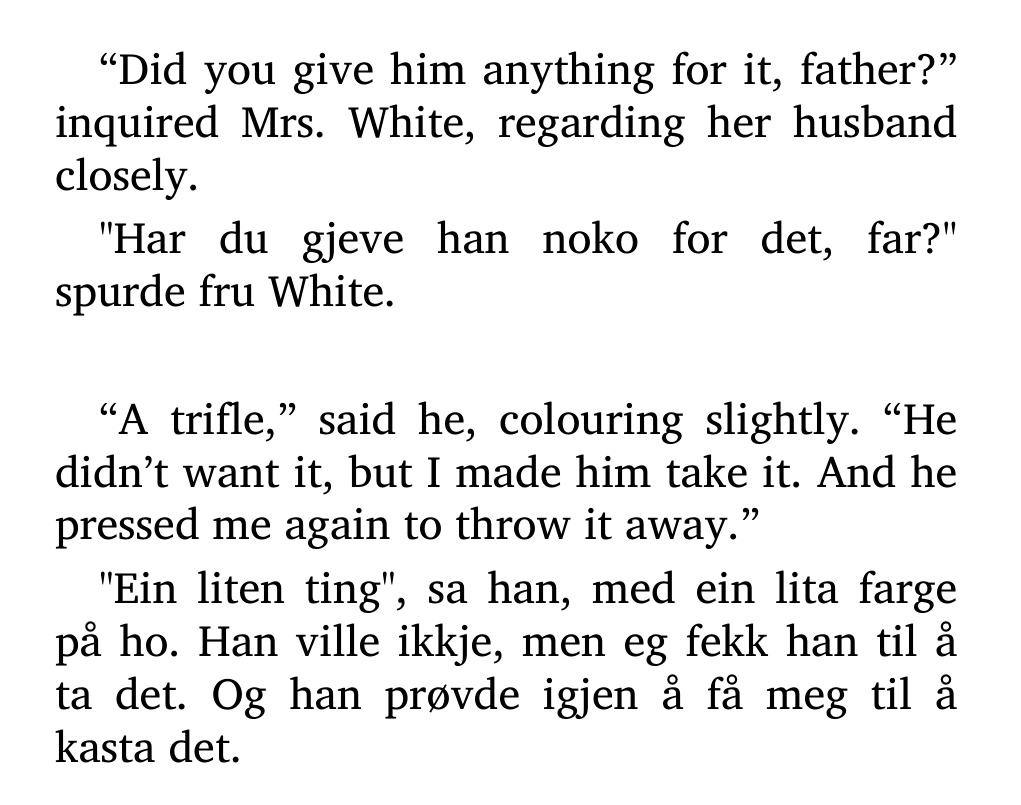

This may not work so well for books with long paragraphs. The pairs are separated by an extra line break. An example of a translated book in bilingual mode:

How to retain formatting

This section outlines the solution for deconstructing a paragraph to sentences and reassembling it in another language. The preprocess_book function iterates XHTML files of the unzipped EPUB and calls preprocess_html. The argument p_tags contains all paragraphs of the given HTML file. The function returns sentence_list with all the sentences extracted from the paragraphs using NLTK and tag_sentence_count is a dictionary that maps the number of sentences to the paragraph’s position.

def preprocess_book(htmls):

html_objects = []

for html in htmls:

sentence_list, tag_sentence_count = preprocess_html(p_tags)

html_objects.append({

"html_name": html,

"sentence_list": sentence_list,

"tag_sentence_count": tag_sentence_count

})

return html_objects

The preprocess_book function returns a list of objects representing the HTML files. Such an object holds an insert-order sentence_list and the dictionary holds the information about the original sentence count per paragraph.

The code in apply_translated creates a deep copy of the tags to avoid overwriting the original EPUB and replaces the paragraphs’ strings with the translated sentences according to the numbers in tag_sentence_count.

def apply_translated(translated, p_tags, tag_sentence_count):

new_tags = copy.deepcopy(p_tags)

begin = 0

for index, tag in enumerate(new_tags):

sentcount = tag_sentence_count.get(index)

if sentcount:

tag.string = ' '.join(translated[begin:begin + sentcount])

begin += sentcount

return new_tags

One may ask what happens when a model returns a different number of sentences, which could cause many other sentences to end up in a different paragraph. Well, I did not consider this case until now. The entire logic could be simplified by inserting paragraph indicators in the sentence list. This logic was made under the assumption that several sentences could form a longer input.

Language codes

There is one interesting issue that stems from the need to work with hundreds of languages. Even the two currently implemented models use very different language codes. Finnish is denoted as __fi__ in the M2M100’s tokenizer while in NLLB200’s tokenizer, the code is fin_Latn. The tokenizer’s language codes can be acquired in code:

def get_language_codes():

tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_path)

return tokenizer.additional_special_tokens

A user must be able to select the language without searching for the specific code in hundreds of languages. Some ISO standards exist for language identification, namely ISO 639-3 with a helpful website search. I downloaded a dataset with these codes in three frequently used formats and the full english names. The codes from model’s tokenizer are compared with the contents of language_codes.json and any missing languages are reported.

Data in language_codes.json:

{

"alpha3-b": "geo",

"alpha3-t": "kat",

"alpha2": "ka",

"English": "Georgian"

},

{

"alpha3-b": "ger",

"alpha3-t": "deu",

"alpha2": "de",

"English": "German"

},

A dictionary maps the tokenizer codes to the language codes from JSON. The dictionary contains only the supported languages of the given model. The find_by_code function iterates over the JSON contents and returns the first occurrence that starts with link_code.

def map_languages(model_langs, json_path):

with open(json_path, 'r') as file:

json_all_codes = json.load(file)

mapped_json = {}

for model_key, link_code in model_langs.items():

json_entry = find_by_code(link_code, json_all_codes)

if not json_entry:

logging.warning(f'Language code missing: {link_code}.')

continue

mapped_json[model_key] = json.loads(json.dumps(json_entry))

mapped_json[model_key]['model-key'] = model_key

return mapped_json

The mapped data can be searched by any of the codes or the english name. I created a console search that returns all languages that have any of the identifiers beginning with the user’s input.

Select source language (start typing):

acq - Ta'izzi-Adeni Arabic - acq_Arab

tam - ta - Tamil - tam_Taml

taq - Tamasheq - taq_Latn

taq - Tamasheq - taq_Tfng

tat - tt - Tatar - tat_Cyrl

tgk - tg - Tajik - tgk_Cyrl

tgl - tl - Tagalog - tgl_Latn

user input: ta

This works even for the case when one language has different scripts (taq_Latn, taq_Tfng). User types until a single language is matched and confirms. The language code for the model’s model_key is set as either the source language or target language parameter. The search logic is out of the scope of this post.

Initialisation order

The beginning of a translation workflow begins with the creation of a translations object that assumes the role of a manager class for all implemented models.

translator = translations(json_settings.get('selected_model'))

model_langs = translator.get_language_codes()

mapped_langs = language_codes.map_languages(model_langs, json_codes_path)

The creation of translations does not yet load the model file. Instantiating a model takes a few seconds and should ideally be done only once. The target and source languages should be known beforehand. The function get_language_codes bypasses the constructor invocation (in the model class):

def get_language_codes():

tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_path)

return tokenizer.additional_special_tokens

class Model:

def __init__(self, source_lang, target_lang):

When the languages are selected, the model can be instantiated.

source_lang = language_codes.search(mapped_langs, 'Select source language')

os.system('cls||clear')

target_lang = language_codes.search(mapped_langs, 'Select target language')

os.system('cls||clear')

print("Loading model...")

translator.instantiate_model(source_lang, target_lang)

For a complete overview, here is the NLLB-200’s constructor. Notice the AutoTokenizer and the arguments:

def __init__(self, source_lang, target_lang):

self.target_lang = target_lang

self.model = ctranslate2.Translator(model_path, 'cuda')

self.tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(

model_path,

src_lang=source_lang,

clean_up_tokenization_spaces=True)

Model issues

Even machine translation models tasked to translate a short text sometimes tend to introduce artifacts, repetitions, or cut out a part of sentence. One example is the bilingual text screenshot where the last part of the first sentence is not reflected in the translation.

Some minor issues can be fixed with arguments supplied to the tokenizer, pipeline or functions. So far, I disabled unknown tokens to avoid unicode artifacts, adjusted beam size and set repetition penalty, otherwise there would be pages filled by a single word.

def batch_process(self, text):

input_tokenized = self.tokenizer(text, return_tensors="pt",

padding=True, truncation=True)

...

results = self.model.translate_batch(source, target_prefix=target_prefix,

beam_size=beam_size, repetition_penalty=1.4, disable_unk=True)

There are a lot more arguments for soft or hard limitation of the model’s output. I did not look too deep into the options. Certain issues cannot be solved, but they can be minimised. It would be helpful to set up a semi-automated comparison of different models and parameters if I get to optimising the output quality.

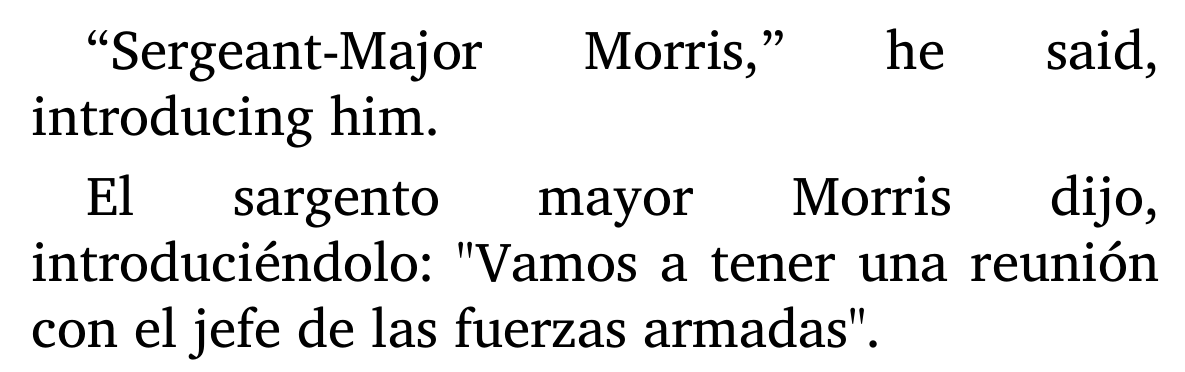

A prime example of hallucination. Here, the word Sergeant led to the addition of head of the armed forces.

Distribution

Packaging the tool into a contained format is not feasible. The dependencies have many versions for different systems. A user has to download the source code, Python and the dependencies specified in requirements.txt. The quantization dependencies could at least be lazy-downloaded with the models.

The models are optional and can be downloaded from the program. The huggingface-hub introduces a convenient way to download the files:

from huggingface_hub import snapshot_download

def download(model_name):

repo = 'BLCK-B/nllb-ctranslate-int8'

folder = appdata / 'models' / 'nllb-ctranslate-int8'

snapshot_download(repo_id=repo, local_dir=folder, cache_dir=None)

Assessment

You can view the project’s source code here.

The main task – EPUB translation – works well. There are many areas for improvement, some of them already noted. For one, sentence detection could be made better and tested on languages with other sentence endings. EPUBs with nonstandard structuring are handled quite well otherwise. Special case is poetry that typically has rows of flowing text that is difficult to process without breaking formatting.

Translation speed is rather slow on a single GPU. If possible, processing more sentences together could not only be faster – the model could also pick up more context. I did not find a reliable way to do that. A simple benchmark integrated in the tool for quality testing would be necessary for any fine-tuning and configuration changes.

Improvements could be made in:

- sentence and edge case handling

- bilingual paragraph processing

- batch processing – speed and context

- quality testing and configuration

- dependencies setup and compatibility

The code is set up for easy extension with new models. Given the speed of developments, it should not be long until a better model comes along. All in all, the translator works well. I conclude from personal testing that the output quality is comparable to the online translator services.